When you’re older than your professor

Today, I have the pleasure of hosting Dr. Noelle Sterne (Ph.D., Columbia University) with a guest post on being an older PhD candidate. Noelle is a dissertation coach and editor, academic and mainstream writing consultant, author, workshop leader, spiritual counselor, and persistent encourager. She publishes articles, stories, essays, and poems in educational, writing, literary, and spiritual venues, and her new column for graduate students and professors appears in Textbook and Academic Authors (https://www.taaonline.net/). In Noelle’s academic editing and consulting practice, she helps doctoral candidates wrestle their dissertations to completion (finally). Based on her practice, her handbook addresses students’ largely overlooked but equally important nonacademic difficulties: Challenges in Writing Your Dissertation: Coping with the Emotional, Interpersonal, and Spiritual Struggles (Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2015). Noelle also helps new “doctors” publish articles and books to further their careers.In her self-help guide, Trust Your Life: Forgive Yourself and Go After Your Dreams (Unity Books, 2011), with examples from her academic practice, writing, and life, Noelle shows readers how to release regrets, relabel their past, and reach lifelong yearnings. Visit her at www.trustyourlifenow.com

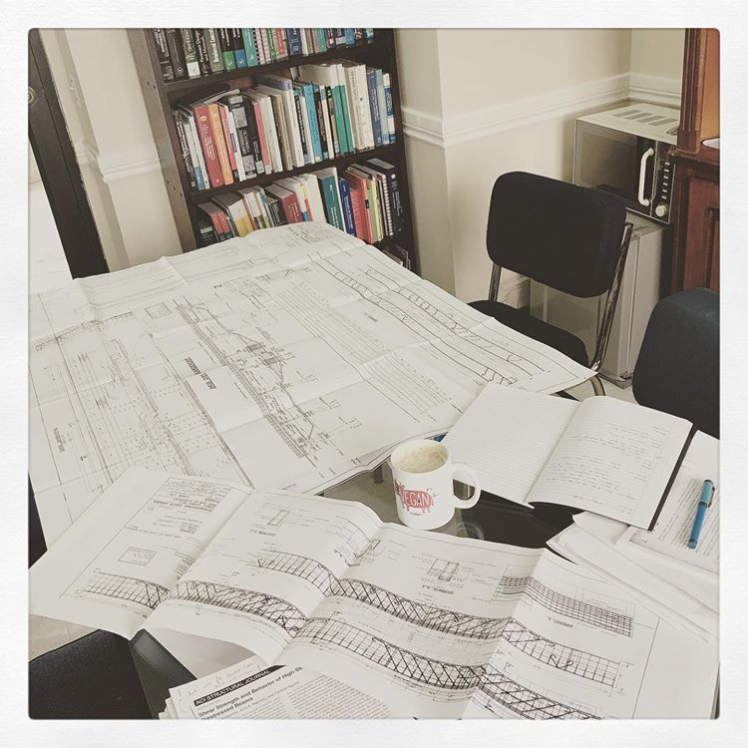

Marlene was one of the brightest and most conscientious doctoral students I’ve served in my academic coaching and editing practice. An older student, in today’s jargon “nontraditional,” Marlene had returned for her doctorate after three of her four kids were grown and self-sufficient. She worked full-time in medical billing, and her youngest was now in high school. So, fulfilling a lifelong dream, Marlene enrolled in a doctoral program. We were working together on her proposal.

When I picked up the phone, Marlene fumed for ten minutes. Her professor had track-changed almost every page of her proposal and added a four-paragraph single-spaced memo stuffed with questions.

I understood why Marlene was so upset. At fifty-two, she had (bravely) just entered graduate school. The professor was younger by at least fifteen years. He challenged Marlene at every turn, and almost at every sentence.

Older Students Are Increasing

Marlene’s situation is not unusual. Like many other older students, she chose an online program to accommodate her full-time job and family responsibilities. With a passionate interest in helping elementary school reluctant readers (as two of her own kids were), she had neglected graduate study for decades because of her family and job.

Most doctoral candidates I help are in their forties and fifties, with a surprising number in their sixties. They often blurt out their ages apologetically, and I immediately congratulate them for their guts, spirit, and drive.

But they find working with younger professors—who could be their children or even grandchildren—difficult. The older students may resent and resist the professors’ critiques and advice, and the issues that arise threaten to sabotage completion of the dissertations.

Why Do I Get All the Critiques?

I told Marlene that her professor’s cries for revisions may have stemmed from one of two main motivations. The first: perfectionism, vindictiveness, pettiness, and a less-than-healthy desire to prove himself and show her who’s boss. He may have also recalled his own tormenting doctoral tribulations and want to extract revenge.

The second motivation is more wholesome. The professor may have pushed for revisions because he recognized Marlene’s abilities and wants a quality work. His comments aren’t personal, I told her, and he’s not out to get you. He wants to help you live up to your potential. Probably too, he sees a publishable spinoff (with an acknowledgment to him) in your postgrad future.

From the professor’s side, dissertation advisor and distinguished sociologist Michael Burawoy (2005) candidly observes how he formerly handled his advisees:

I used to make detailed comments that would go on for pages and

totally overwhelm and even paralyze you. Sometimes you would never

come back. It was rather disingenuous of me to complain about your

retreat since I suspect that my barrage aimed to establish my authority,

my credibility as a young sociologist—with little thought as to what might be

helpful to you. (p. 47)

Burawoy’s confession is admirable. If, though, you’ve received critiques such as he describes or Marlene received, whatever you do, don’t act like an irate graduate student I heard of. Without an appointment, he stomped into the chair’s office, threw down the marked-up manuscript, which he’d peppered with a brigade of sticky-note soldiers ready for battle, and argued with every one of the chair’s points. Needless to say, the candidate only reaped more endless-revision reprisals.

As an Older Student, You Have Advantages

As an older student, you may not realize that some things are on your side. Research confirms you’re more persistent than younger students in reaching academic goals, more self-reliant, and more purposeful in mastering the required skills (Bertone & Green, 2018; Deshpande, 2016; Dunn, Rakes, & Rakes, 2014; Offerman, 2011).

Offerman (2011) notes:

The contemporary doctoral student is older, more mature, and brings into the learning situation a wealth of real-world, career experience. The effective faculty member understands this and expects to learn as well as to teach, to act more as a colleague at times than a supervisor. (p. 27)

Whether or not your professor adheres to such an ideal perspective, you can navigate successfully through your doctoral experience by keeping several things in mind.

What You Can Do

- Forget age and age comparisons (“He’s half my age, already tenured,

published in five top journals, with twenty-three grants!”). Remember why you’re a graduate student and what your degree will do for you. - If you’re an online student, your status can be a blessing—you don’t have to stare into that impossibly fresh face two or three times a week (unless the professor insists on Zoom conferences).

- Granted you have extensive experience in your field, but swallow your pride and compress your knowledge. You may know a lot more about your topic than your professor. But your professor likely knows what’s more dissertation-acceptable.

- If, though, especially if yours is an applied dissertation, some of the professor’s critiques are likely based on inexperience with your research site. So verbalize your corrections and cite your experience diplomatically. “Professor __, I realize you may not be familiar with . . . .” (They have egos too!)

- After you get back the blood-red track-changed paper, arrange a meeting.

Admit your doctoral frailties, be open to the critiques, and ask for clarification. As Cassuto (2013) says, good advisors and chairs collaborate with their students. If you don’t understand, persist. - Don’t whine. Your professor has his own problems.

- In person, phone, email, or text, act professional, as you do on your day job. You will gain the professor’s respect.

- Remember other situations, such as issues with family or colleagues, in which you responded reasonably and creatively. Applying your skills can help you weather the tempests of an advanced degree program, and especially the dissertation.

- Treat yourself with self-respect. You have a right to your professor’s guidance and explanations (after all, you’re paying for it).

- Seek outside help if you feel you could really benefit (a peer, a recently-graduated colleague, a coach, an editor).

- Do the work diligently and do it well.

As an older graduate student, you’ve plunged into a highly challenging educational path that others half your age often avoid. So, wear your age proudly, be grateful for your life experiences, and, when you’re older than your professor, use your previous encounters, interpersonal skills, and infinite patience to complete your long-dreamed-of degree.

References

Bertone, S., & Green, P. (2018). Knowing your research students: Devising models of

doctoral education for success. Postgraduate Education in Higher Education, 471-498.

Burawoy, M. (2005). Combat in the dissertation zone. American Sociologist, 36(2),

43-56.

Cassuto, L. Remember, professor, not too close. Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Not-Too-Close/138629/

Deshpande, A. (2016). A qualitative examination of challenges influencing doctoral

students in an online doctoral program. International Education Studies, 9(6), 139-149.

Dunn, K. E., Rakes, G. C., & Rakes, T. A. (2014). Influence of academic self-regulation,

critical thinking, and age on online graduate students’ academic help-seeking. Distance Education, 35(1), 75-89.

Offerman, M. (2011). Profile of the nontraditional doctoral degree student. New

Directions in Adult Continuing Education, 129, 21-30.